Today we’d like to introduce you to Peter Stuhlmann.

Peter, please kick things off for us by telling us about yourself and your journey so far.

My adventure as an artist began precariously enough–I was born into a family of accountants and financial types. I was different. Where those around me could think in, and relate to, numbers I thought in pictures. Of course at the time I didn’t know that not everyone could do this, I just assumed. Wanting to make pictures was as natural to me as walking.

Before I get too far ahead of myself I should mention that the actual matter of pencil to paper spark cam when I was four years old, suffering a summer’s broken leg in Hamburg Germany, where I was born. To keep from my driving them crazy, my parents handed me a large stack of paper and some coloured pencils and expected that I should now amuse myself. I did. Obsessively, in fact–and really haven’t stopped since. A child drawing and colouring certainly isn’t anything unusual, they all do. But they all don’t manage images that look like something, which apparently I did.

It started with animals, poring over magazine and book, copying and emulating. For many many years I stuck to pencil, with which I felt I had the greatest amount of control, and because it was cheapest. There would be a few hesitant watercolours over the years, but nothing to suggest I would become an artist. Not one was corner-to-corner paint. Regardless, my education was under way. Drawing, after all, is the corner stone to painting, whatever one might hear to the contrary.

Painting simply wasn’t something you did in my family unless you planned on being homeless. Now as convenient as it might be I can’t leave that stone on the shoulders of my family, as there are plenty of very successful and relevant painters who were not urged to pursue the arts in childhood. The truth is it genuinely never occurred to me. Perhaps, unconsciously, I even avoided it, as I feared it might have ruined the “this is mine” component of painting. I do remember walking by an art class at a local college whose art studio windows just happened to be at ground level and visible to the public, and I remember looking at all those easels, the instructor hovering nearby like a raiding wasp, and I thought “This ain’t for me.” Art, in my world, was synonymous with freedom, not subject to grinds and deadlines and institutional expectations.

I should mention, critically, that we did not stay in Germany. Rather emigrated, in 1970 to Canada, where I have been ever since. The bulk of my life in the eastern part of the country, more recently the west. What I learned while being completely unaware I was learning it, was the importance of place and landscape that would show up later. Having moved at age 7 I would forever thereafter feel displaced, questing the notion of place to identity. Having moved to a country that measures travel in days, not just hours and minutes, and that was so much more in tune with nature and the natural forces that shape it–landscape would forever be the real subject of what I would go on to paint. In all its moods, not just the calm, sunlit ones. This landscape and climate has edge, could bite if you weren’t careful. I wanted that in my art also. But for now, I was simply observing and absorbing.

In many ways, in this respect I share a measure of commonality with the American Mid-west and the cities there. Unlike New York or California, the Mid-west is much closer to some of the harsher realities of willful climates–cold that can tear the flesh, wind that can toss you about at will; as well as what comes with heat and drought. Cities aren’t so much built there as carved, will against will, from the surrounding landscape. It’s not always pretty, and neither should art be.

I began poring through art books, discovering the famous historical painters therein. While I became a fan of many, there are two or three–and their associated movements–that resonated far more than the others. Seurat (Chicago is home to my favourite painting in the whole world–“A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” by Georges Seurat. It had, well, everything. It had an every-day subject, something to which every-day folks could relate, and yet it was spectacularly revolutionary and unexpected. It had dots.

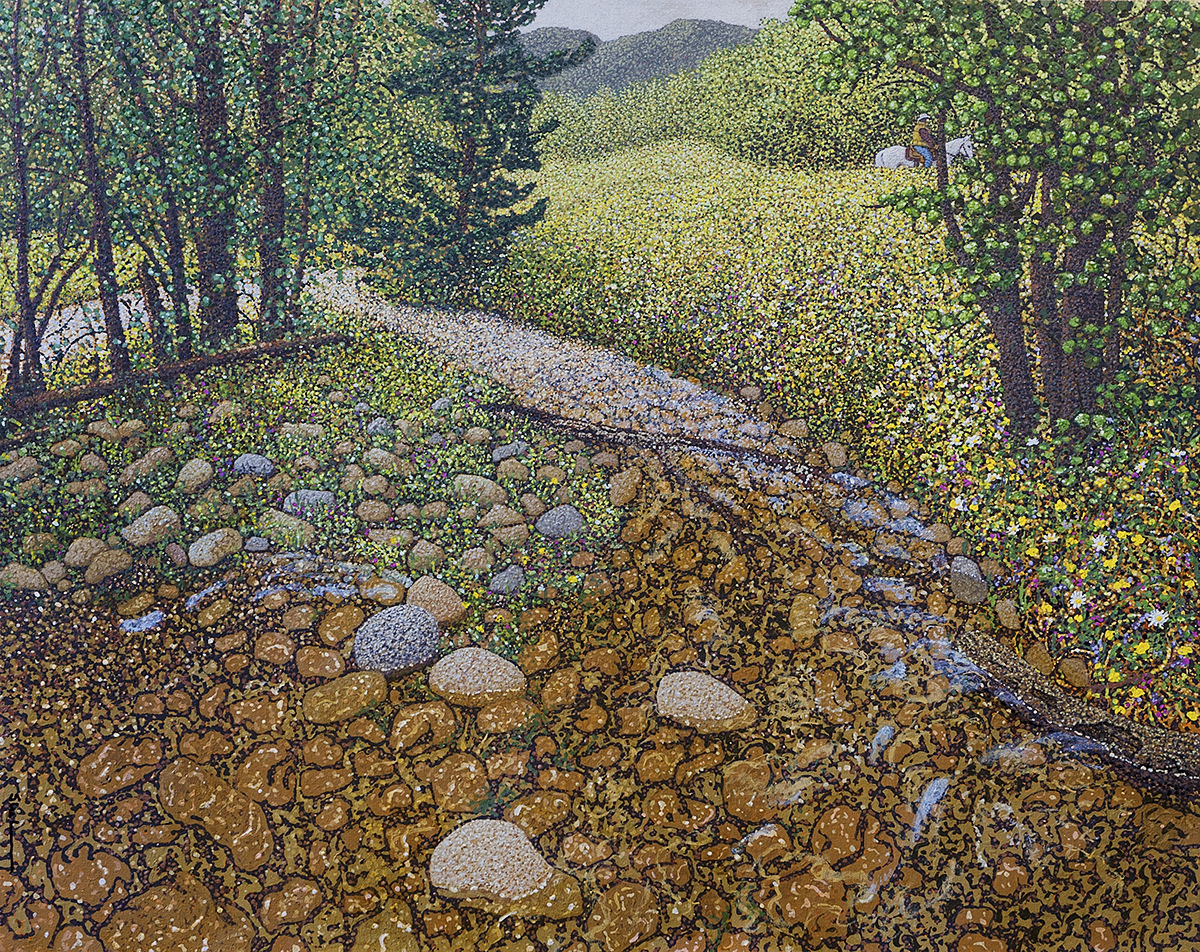

I have no idea why I am obsessively (to a compulsive degree) drawn to making little tiny marks, regardless of canvas size, but I am. It makes me happy, in a zoned-out meditative way. Seurat painted in dots–or, more accurately, in little marks that (colour theory and optical blending notwithstanding) had the remarkable ability to create a bristling sort of energy you might imagine at an atomic level, energy perpetually on the verge of being released. There is nothing static about that picture, which in itself is a remarkable achievement.

The second painter was Grant Wood. Through him I discovered American Regionalism, an amazing inroad to the notion of place in painting. Now I’m not talking about geographic particulars–although those do matter–I’m rather talking about the landscape that’s carved into people by place. There is a heroic stoicism to all his work, which is yet undercut by a certain type of tension never quite resolved. Man tested is a recurring theme. That notion is of course incredibly rich in terms of potential, something not easily exhausted.

I did not begin painting complete pictures until after 2007, when I made the move out west. To earn my keep I’d ventured into the culinary arts (even did a stint at The Culinary Institute of America), and cooked for many years. Interestingly, while I certainly loved being in the “trenches” with other kitchen folk, I never felt one hundred percent that I belonged. Too much of a solitary soul, I suppose.

That first winter out west, the kitchen game being of a seasonal nature out where I was, I began to paint. Little ones at first, an inch or two by an inch (literally), to gradually larger ones as I gained confidence. I paint much larger now, of course, and I paint full-time. In dots, always in dots.

Can you give our readers some background on your art?

I paint exclusively in acrylics on canvas, with very tiny brushes, my nose never more than an inch or so from the canvas. In dots–it’s the fundamental unit of expression, more so than line even. In that sense then, I’m an iterative painter, I add and add until I’m done with it, rather than wiping or scraping paint away. At a personal level, I suppose this has to do with the idea of tending, or meditating–you turn the music up really loud and disappear into the act of making a painting. At that point, what I’m painting is almost secondary in importance, letting the picture decide where to go next.

The what, or subject, is only ever a bit of a trampoline, launching into a riff or thematic development, usually spurred on by the last picture. I’m always, in my head, about a painting and a half ahead, looking at the live one in front of me “Oooh, that’ll work really well in the next”, Or “hey, there’s an idea!” again meant for a future painting. In that sense, I’m completely against the notion of people advocating living in the moment–I have no such moment. Time and temporality can’t be separated into discrete stages in my inner world, and so I hope (more of a flow, really) all over the place where time and memory are concerned. I suppose it’s true that an artist is always painting the past, in the sense they integrate and distill memory and experience into something produced now-ish, but internally even that distinction resists.

In the natural world, the subject is the land, and my daily walks with dog and wife, and the hours spent poring over every leaf and stone and change in weather–I try to record it all. I take tons and tons of photos, but will only rarely look at them while painting. I really don’t even like to move my head from the picture to look at something like a photograph, I find it terribly distracting. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, I find that relying on photos would take away from the narrative thread in a painting, or otherwise dilute its intentions.

My pictures intentionally have no message. Given that I am one of seven billion hopping about aboard this little space marble, the idea that I alone should have a message for anyone other than the occasional “Oh, I wouldn’t eat that” is frankly absurd. Furthermore, I really try to shy away (been very successful at it so far) of the cult of the artist as special, informing being as much as possible. I simply don’t have the air for that wind sock. Now this is not to suggest I’m not saying anything, I suppose I am, in the way I paint.

With my dots I’m saying that paintings take time to make, a lot of time, a daunting amount of time, which can then be argued tries to resist contemporary modes of discourse and commerce, which wants everything as fast as possible. I want to slow everything down, which–true enough–is its own form of conceit, however minor. I don’t want to consume, I want to experience. And yes, I don’t think it would hurt other people to try that either. But that’s as far as I’m going by way of suggestion.

On a personal level, I’m hunting. For the perfect tone, and the perfect picture. They don’t exist, of course, but it’s important to try, and to keep trying. It keeps me in the world.

What responsibility, if any, do you think artists have to use their art to help alleviate problems faced by others? Has your art been affected by issues you’ve concerned about?

There’s a great question! Absolutely, the role of artist has changed. Given what can in best terms be described as tumultuous times, and the challenges we face–nowhere more so than in the minority and marginalized communities–the artist is incredible important. Art is what gives humans their humanity. In that sense, the artist is vital. I’d say it’s almost a civic duty to lend a voice to positive change and outcomes, and to preserve our common decency. It’s also to give voice where maybe there isn’t any. Often, when public discourse has been co-opted and perverted–think media, public debate, the artist’s voice is one that can hopefully prevail.

That said, I think I’m failing miserably at it. The challenge is to do it in a way that’s genuine, without inadvertent parody, or heavy-handed sincerity–the last thing I want is to cheapen things. A very large chunk of me believes that you put your head down and do what you love, even if you can’t immediately see how that affects anyone else. Is there something to be said for refusing to be one of those blowing things up? That might have to do until I figure things out.

What’s the best way for someone to check out your work and provide support?

The best place to see my work is on Facebook and Instagram. I do have work in a great little nearby gallery–Gallery Odin. http://www.galleryodin.com/peter-stuhlmann.html

Contact Info:

- Phone: 1-679-3799

- Email: pdstuhlmann@yahoo.ca

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/peterstuhlmann/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/stuhlmann.peter

Getting in touch: VoyageChicago is built on recommendations from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you know someone who deserves recognition please let us know here.